10 Things You Probably Didn’t Know About Black History Month

Every February, America recognizes the struggles, achievements and contributions that the African-American community has made to honor its ancestry and recognize the advancements and innovations that have shaped our lives and society. Its founding was aimed at increasing education and awareness on the subject at a time when forces actively tried to write famous figures such as Crispus Attucks and Harriet Tubman out of the history books. Even though this annual celebration may seem familiar as an annual tradition, its official acceptance is relatively young and faced scrutiny and criticism including by those who were responsible for its very foundation.

- 1

The annual observance was created by Carter G. Woodson

Woodson was a lifelong historian and educator who dedicated his life to making sure that African-Americans contribution to history and society were part of the mainstream curriculum. A graduate of the University of Chicago and the second African-American to receive a doctorate from Harvard University behind W.E.B. Du Bois, he and several other noted leaders founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (now known as the Association for the Study of African-American Life and History) in 1912 and The Journal of Negro History in 1916 to educate the public on the achievements and contribution of the African-American community. Both made several notable advancements, but Woodson wanted to do more and dedicate an official time of observance to continue its reach across society.

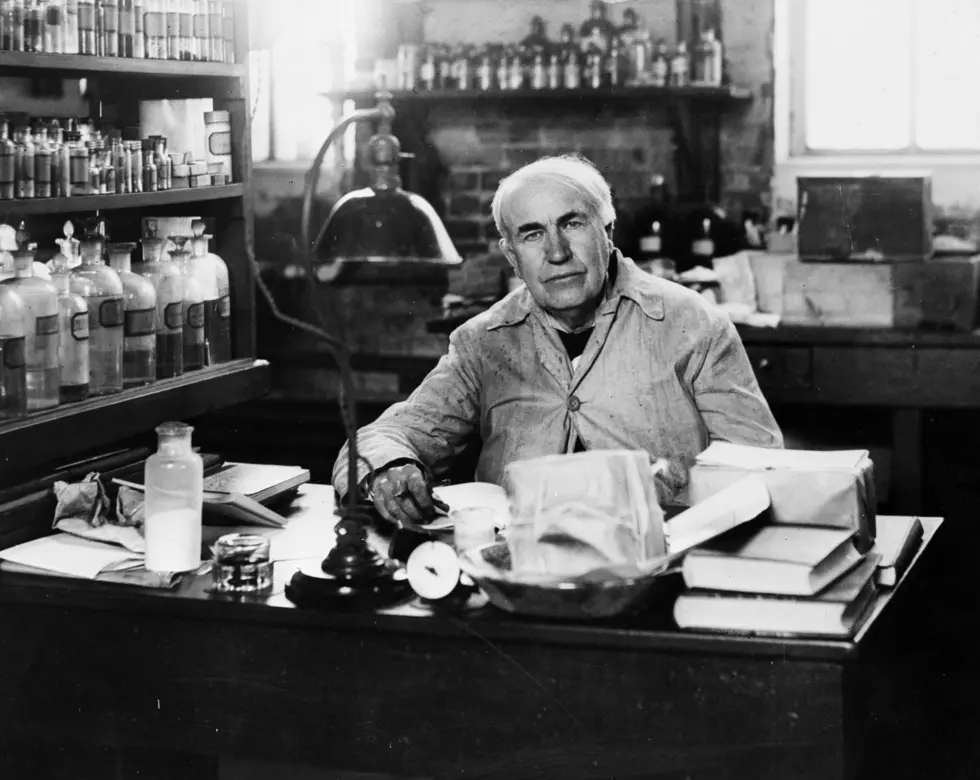

Hulton Archive, Getty ImagesHulton Archive, Getty Images - 2

It was originally a week-long observance

Woodson wanted to reach a wider audience and involve communities in a period of observance, awareness and remembrance. According to the ASALH, he started in 1924 with the establishment of Negro History and Literature Week, later renamed Negro Achievement Week, by spreading the word through his fraternity brothers as a graduate member of Omega Psi Phi and other civic organizations. Two years later, he expanded on the idea by issuing a press release on behalf of the Association announcing a week in February as Negro History Week.

Open Clipart LibraryOpen Clipart Library - 3

February was chosen because of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass' birthdays

February wasn't just arbitrarily chosen by Woodson as a time on the calendar to dedicate to his special week. The birthdays of President Abraham Lincoln and abolitionist leader, writer and orator Frederick Douglass fell in the month of February and Woodson thought their days would serve as the perfect foundation for Negro History Week. Both birthdays were honored with celebrations, but Woodson felt these symbolic days perpetuated the very cycles of ignorance that his work and observances sought to end. He felt history was made not by great individuals but great people and a study and observance of the race as a whole and their contribution to society was more important.

Hulton Archive / Getty ImagesHulton Archive / Getty Images - 4

Like all observances and holidays, it also suffered from early forms of commercialization

The week-long observance was met with great fanfare and Woodson and his group received a great deal of demand for materials from schools and civil organizations. The demand was so great that impostors started sprouting up that pushed a false notion of history and heritage. Books from traditional publishing houses that largely ignored African-American history tried to publish books quickly to meet demand books and “mushroom presses” churned out poorly checked and researched history texts. Woodson issued public warnings about such charlatans and substandard materials and personally worked to make sure that organizations and schools received well-researched books and knowledgeable experts.

Chicago Public LibraryChicago Public Library - 5

Woodson wanted to expand Black History Week to Black History Year

Of course, Woodson didn't see his observance as just a weekly or even a monthly celebration worthy of attention just once a year. He saw it as an observance unbound by time. His efforts to increase awareness of African-American history were meant to reach to the rest of the school year and he pressed communities and schools to expand their education efforts beyond the boundaries of Negro History Week. He worked tirelessly to achieve his goal until his death in 1950.

WikipediaWikipedia - 6

Woodson wasn't widely recognized for efforts for several years

Despite all of Woodson's hard work, he didn't receive the true credit he deserved for his efforts to preserve and educate the nation on African-American's contribution to history for quite a awhile. Towards the end of the 1960s, author and historian Noreen Hale compiled Woodson's work in his first biography. Even though she characterized his writings as colorless and vague, his words and efforts stood as his crowning achievement and helped create “the fusion and vacillation between various tenets of both conservative and radical 'schools' of black thought.” This and other subsequent examinations of Woodson's work would earn him a place in history as a driving force behind one of the nation's earliest movements for the advancement of cultural studies and raising the awareness of their importance in the examination of history.

U.S. Stamp GalleryU.S. Stamp Gallery - 7

Gerald Ford was the first president to issue an official message on Black History Month

The 38th president often gets credit for expanding the observance from week to month, but the movement for expansion began long before the start of his presidential term. According to the ASALH, communities in West Virginia expanded the celebration to a month-long observance in the 1940s and cultural activist Frederick H. Hammarurabi encouraged communities through his cultural center in Chicago to spread the observance to the rest of the month. Soon, members of the ASALH followed suit and the celebration spread to a month-long celebration by the mid 1970s when President Gerald Ford issued the first official presidential message encouraging citizens to participate in the observance and “the message of courage and perseverance it brings to all of us.”

Getty ImagesGetty Images - 8

It didn't receive an official proclamation by the US government until 1986

Ford started a worthy tradition of issuing messages on the observance of Black History Month, but it wasn't until 1986 when Congress approved and Ronald Reagan signed the first proclamation recognizing February as Black History Month that it was legally recognized as such, according to the Library of Congress. That same year also marked the first federal observance of Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

Hulton Archive, Getty ImagesHulton Archive, Getty Images - 9

Every president since has issued an annual proclamation for Black History Month

Reagan's signing of the official proclamation also started a new presidential tradition for the month-long observance with each president since issuing a message and a proclamation recognizing February as Black History Month all the way to President Barack Obama. These proclamations not only recognize February as the official month but also set the official theme for each period of observance with 2012 observed as Black Women in American Culture and History. The Library of Congress has compiled a special section dedicated to Black History Month proclamations and messages from Congress and the White House.

Getty ImagesGetty Images - 10

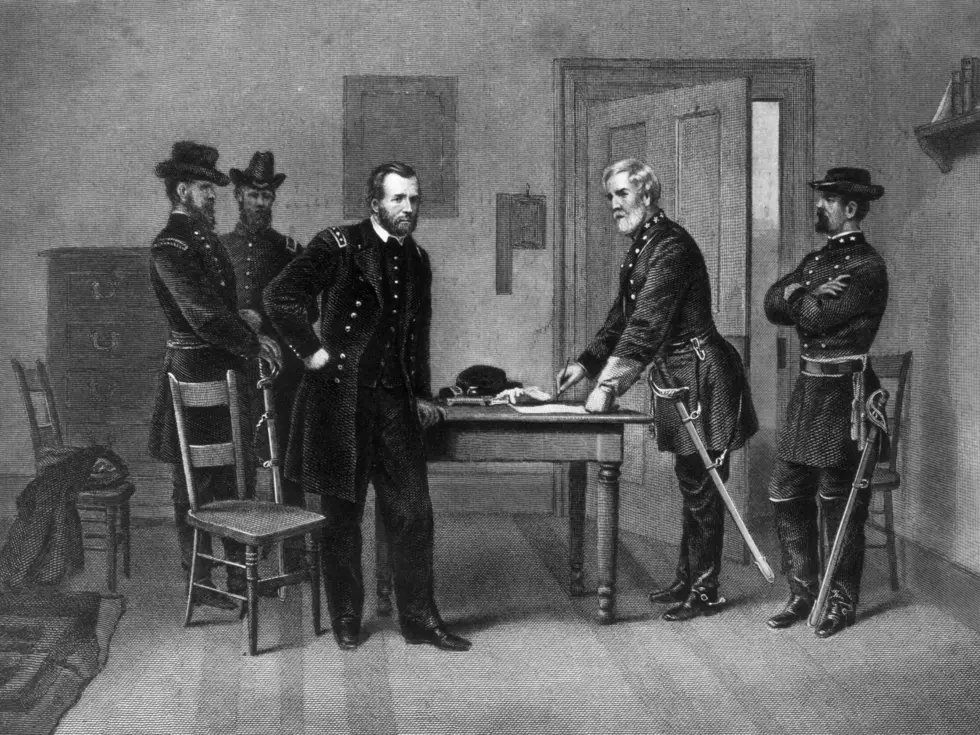

Next year marks a major anniversary for the Emancipation Proclamation and the March on Washington

The 2013 theme for Black History Month will also mark two major milestones in the fight for Civil Rights and African-American history. 2013 marks the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, the official executive order that granted freedom to all slaves in the Union. 2013 also marks the 50th anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s historic March on Washington to the steps of the Lincoln Memorial where he gave his famous 'I Have a Dream' speech to a crowd of 250,000 people.

Mario Tama, Getty ImagesMario Tama, Getty Images

More From KMMS-KPRK 1450 AM